About

“From the first years, the settlers of Plainfield, apparently by common consent, made use of a hill about half a mile west of the present village as a place for the burial of their dead. The date of the first burial there as well as the name of the first person buried there can hardly now, after two hundred years, be learned, for the oldest headstones bear no lettering and the town records are defective.”

– Professor William Kinne

Plainfield Journal, October 1894

“From the first years, the settlers of Plainfield, apparently by common consent, made use of a hill about half a mile west of the present village as a place for the burial of their dead. The date of the first burial there as well as the name of the first person buried there can hardly now, after two hundred years, be learned, for the oldest headstones bear no lettering and the town records are defective.”

– Professor William Kinne

Plainfield Journal, October 1894

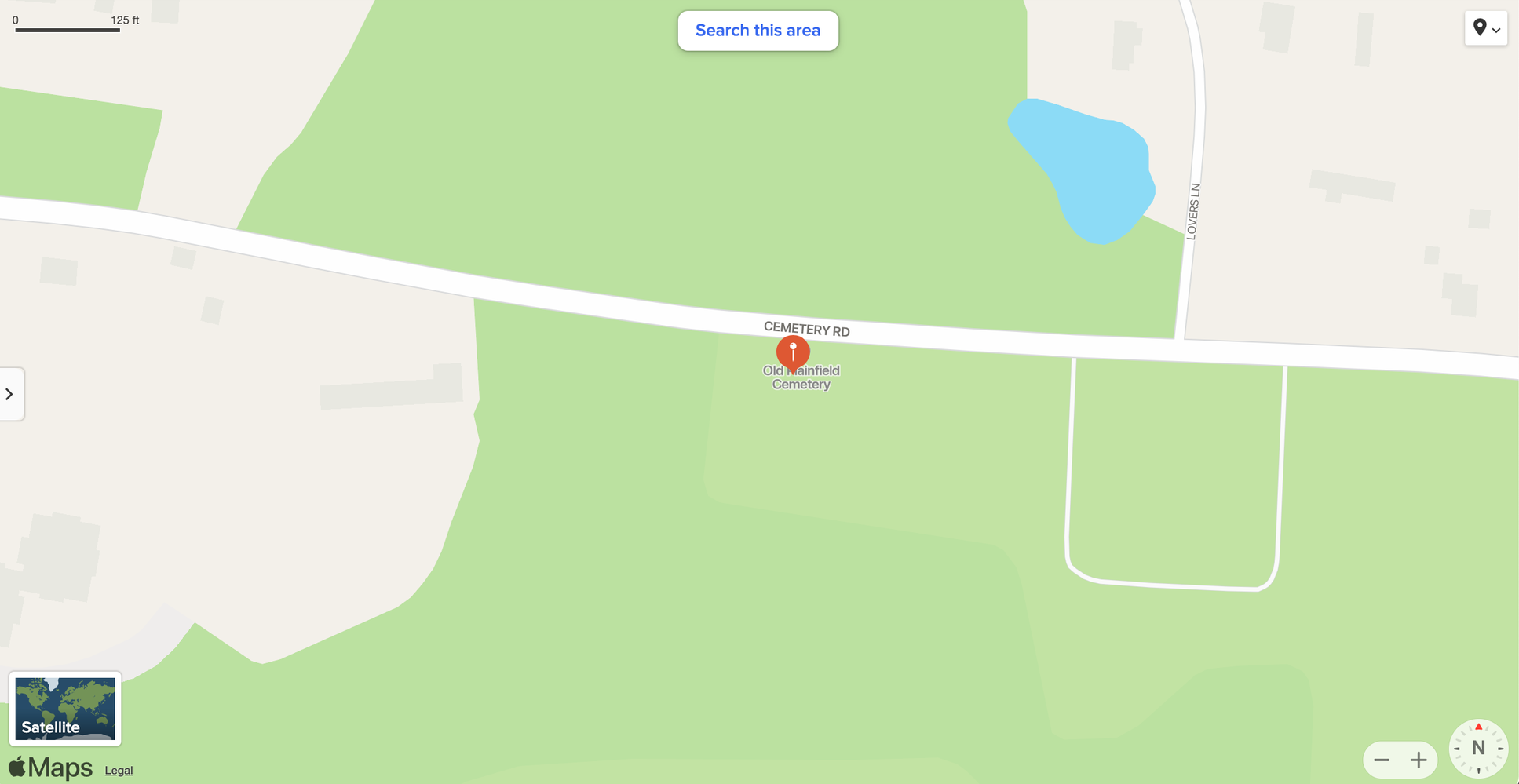

A Town’s Hallowed Ground

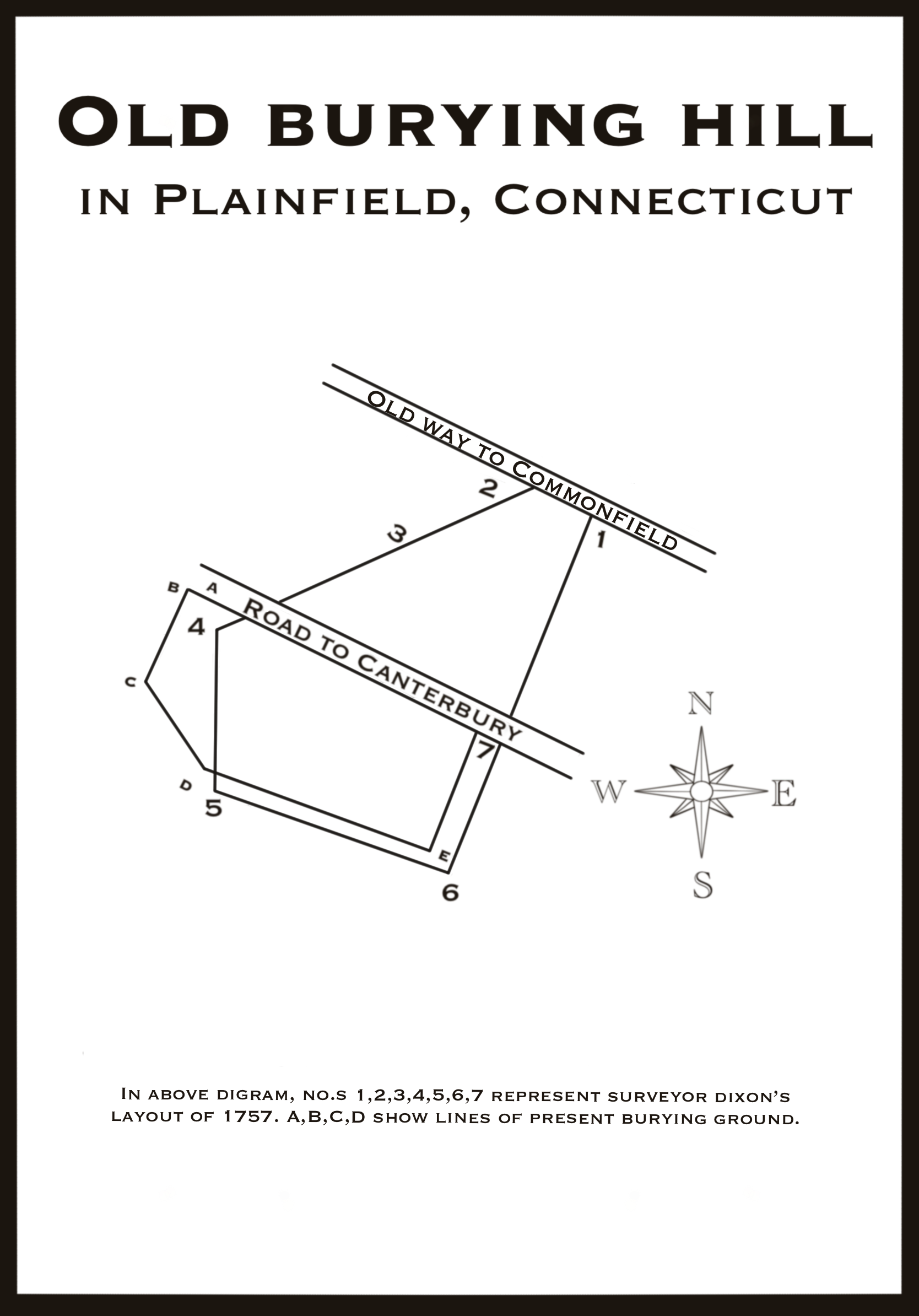

Since its founding in 1711, “Burying Hill,” “Old Burying Grounds,” and “Plainfield Burial Ground” are different names which refer to the same hallowed 2.2-acre public space now referred to as “Old Plainfield Cemetery.”

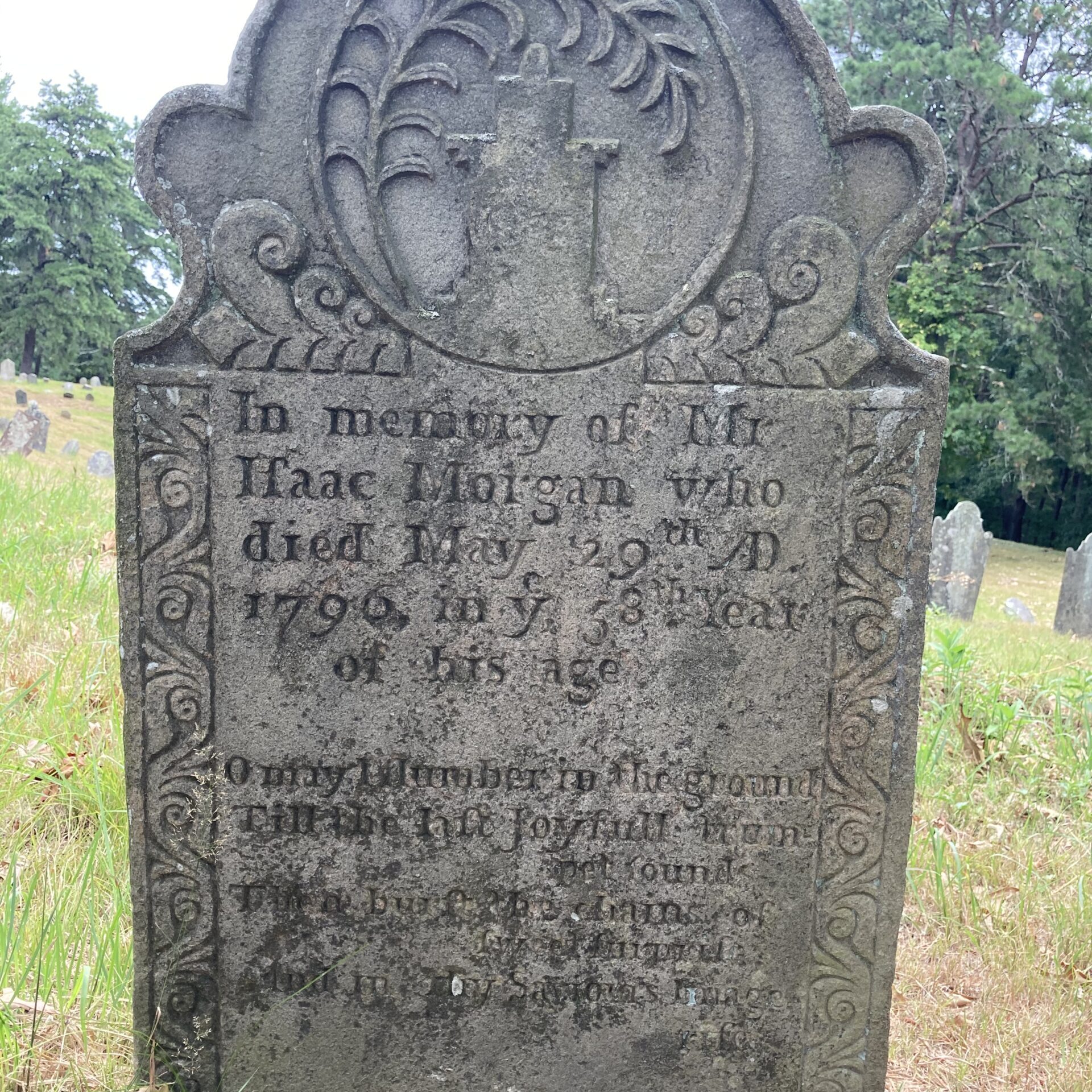

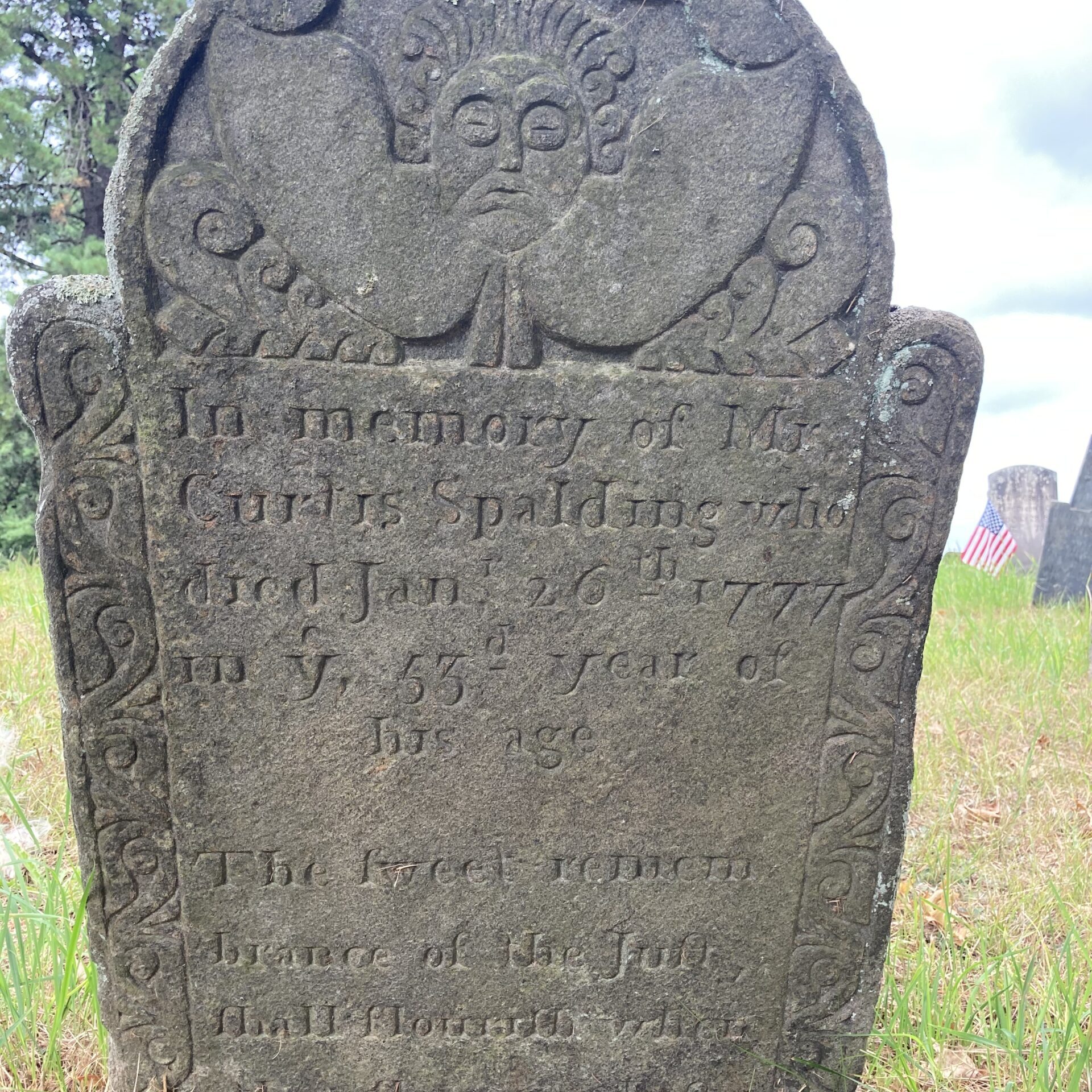

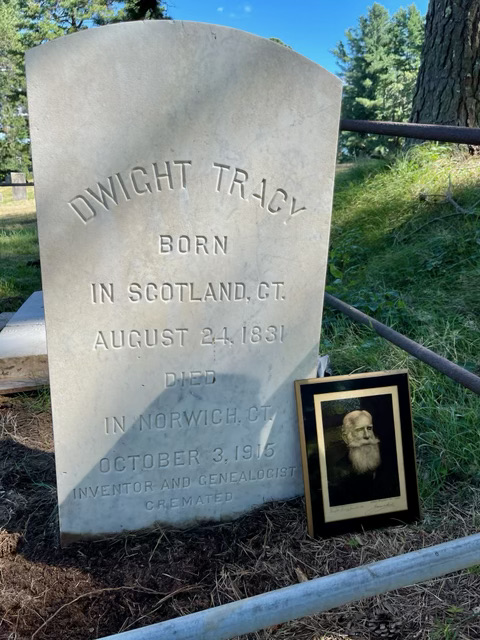

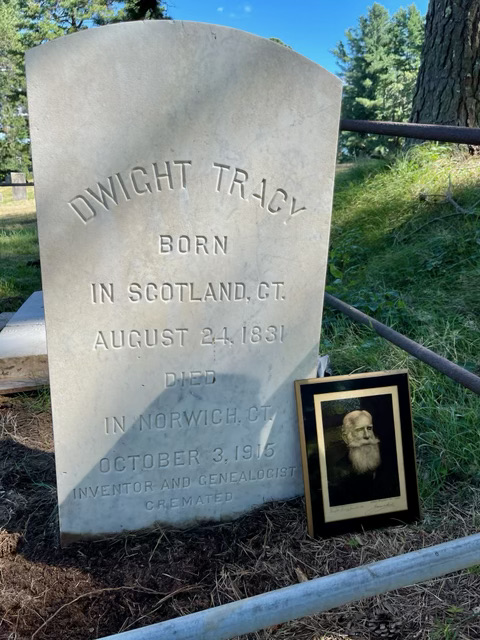

Learning about the lives of each person laid to rest here opens a unique window into local life and national times. Here, more than five hundred burials reflect the diversity and scope of an expanding America, ranging from the oldest legible grave marker dating from Mehitable Blunt in 1721, until the last burial of Dwight Carlton Tracy in 1925.

Today, Old Plainfield Cemetery continues to serve as an unwavering beacon for history, welcoming visitors to this virtual learning platform as well as the ones who choose to venture out for a firsthand site experience.

New Plainfield Cemetery’s Separate Story

Down the hill from Old Plainfield Cemetery is the completely separate and privately owned New Plainfield Cemetery which has its own fascinating story closely linked to the First Congregational Church. Constructed in 1818 and now listed on the National Register of Historic Places, the building’s steeple towers in the distance above the treetops, overlooking both cemeteries. Renowned architect Ithiel Town designed the church before partnering with Alexander Jackson Davis to plan construction of numerous landmark buildings including the U.S. Custom House in Manhattan, now known as Federal Hall, Hartford’s Wadsworth Atheneum, buildings at Yale University and Virginia Military Institute as well as the Potomac Aqueduct in Washington, DC.

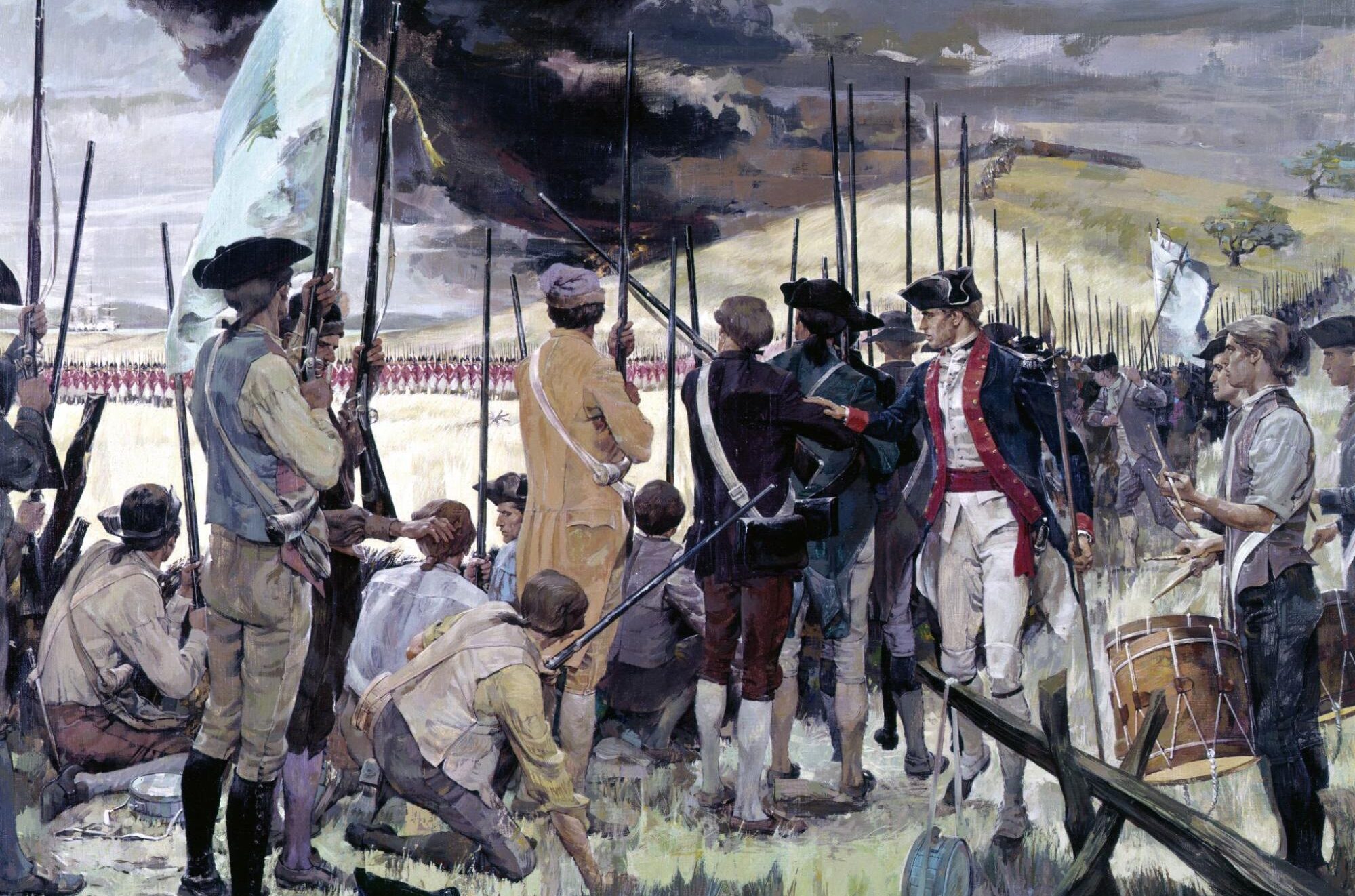

Veterans of Bunker Hill

Distinctive grave markers include those of the colorful Dr. Elisha Perkins, a surgeon at Bunker Hill for the Continental Army who later sold a debunked medical device known as a “tractor” to such luminaries as President George Washington. He died, presumably from accidental poisoning, after consuming one of his own purported medical concoctions.

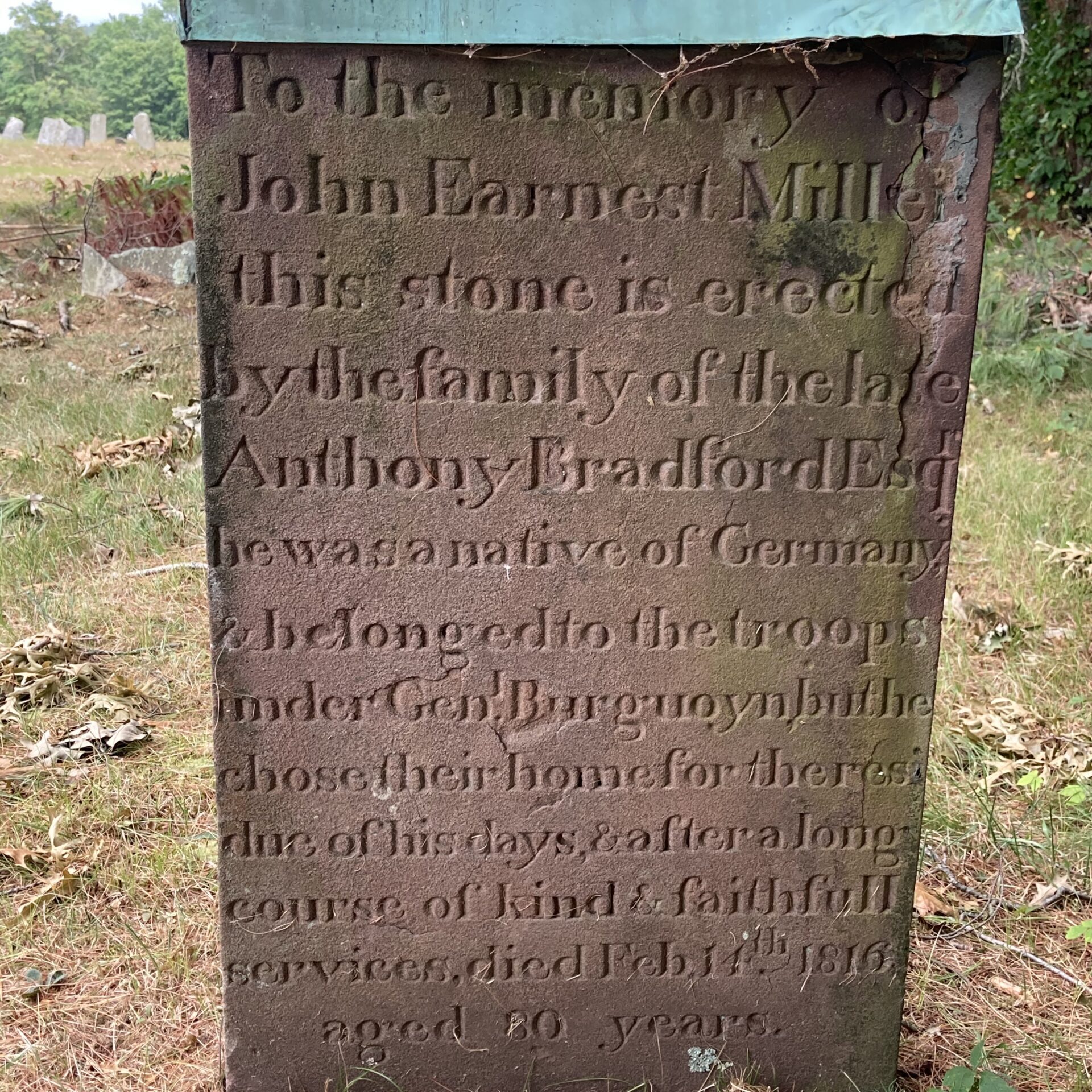

The Hessian Soldier

John Miller has a unique stone here, too. He was a Hessian soldier who served in British General John Burgoyne’s army but chose to call Plainfield, Connecticut home until the end of his days rather than returning to Europe. Surrounding Miller are numerous veterans of the French and Indian War, American Revolutionary War, and the War of 1812.

French Encampment En Route to Yorktown

Abutting Old Plainfield Cemetery’s front side from east to west, Cemetery Road itself appears on National Register of Historic Places due to its vital link along the Washington-Rochambeau Revolutionary Route. Across the street, French military leader Comte de Rochambeau’s French troops encamped in Plainfield starting on June 19th, 1781 while marching to join General George Washington’s Continental Army in New York.

From there, both forces marched together to Yorktown, Virginia where General Charles Cornwallis surrendered in October 1781, effectively ending the Revolutionary War. Returning to France, King Louis XVI appointed Rochambeau as governor of Picardy and Marshall to France until the French Revolution brought chaos there.

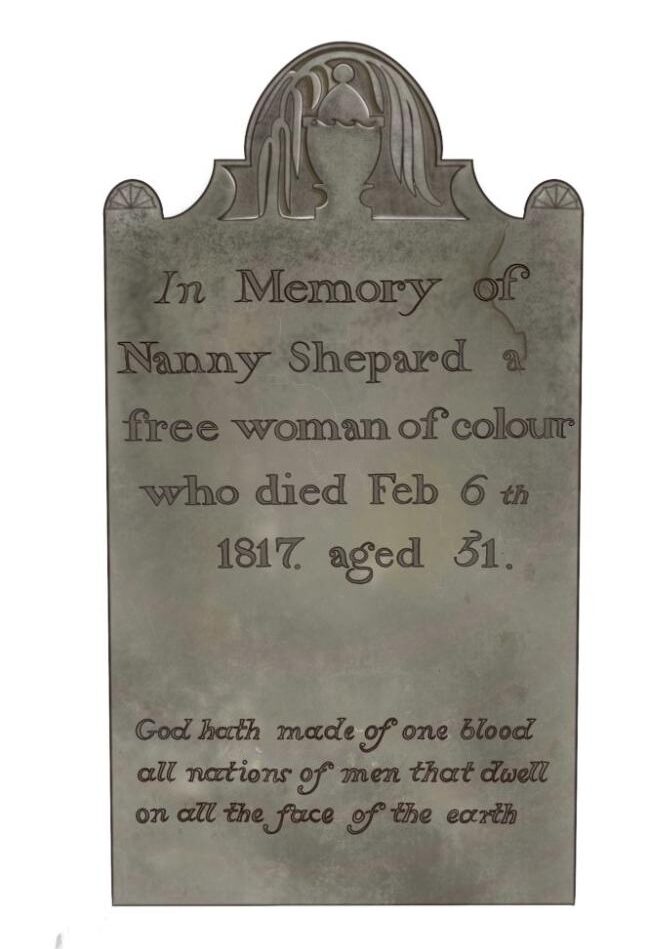

African-American Heritage

Described as a “free woman of colour,” Nanny Shepard is buried towards the middle of Old Plainfield Cemetery. Channeling an especially progressive spirit for the times over two centuries ago, her 1817 stone boldly declares, “God hath made of one blood all nations of men that dwell on all the face of the earth.”

It was not long after that when, in 1832 and less than three miles away, American educator Prudence Crandall, reopened her Canterbury school with a mission to serve African-American girls exclusively. For that, neighbors poisoned the school’s well, broke windows, and set the building aflame, and Crandall’s school soon closed. Today, she’s Connecticut’s Official State Heroine. Decades later, Crandall politely turned down Mark Twain’s offer to repurchase the school building.

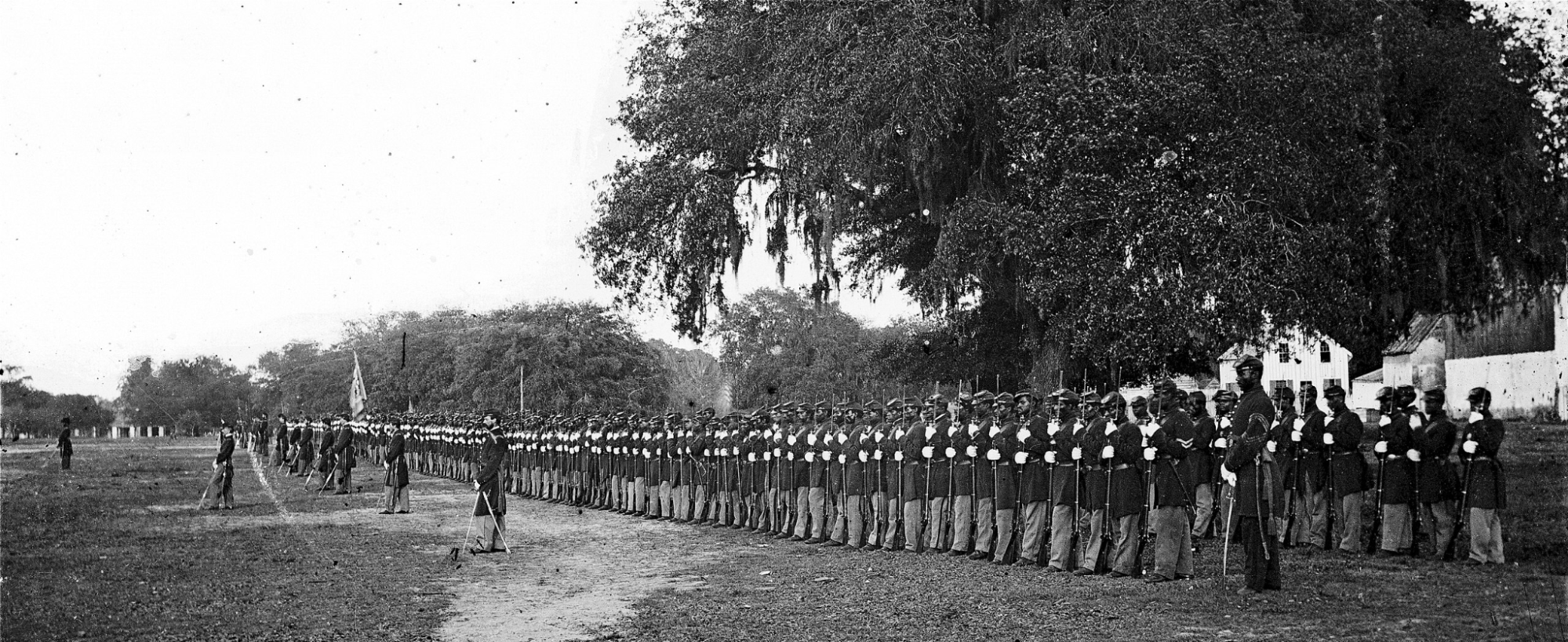

Civil War Heroes

Brothers Charles and Horace Freeman rest side by side at Old Plainfield Cemetery’s western edge, African-American Civil War veterans who fought for 29th Regiment of the Connecticut Infantry. Similar to the Massachusetts 54th Infantry Regiment, depicted in the acclaimed film Glory starring Matthew Broderick, Connecticut had its own division consisting solely of African-American volunteers. The 29th helped secure Union victories in South Carolina, participating in the Civil War’s last days in Richmond, Virginia, until Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s surrender to the Union’s Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Courthouse.