Funerary Art

Early American Gravestones

Gravestones are America’s earliest sculpture. Among early American artifacts they are unique in that each is dated, and most are found in their original settings, surrounded by similar objects from the same period. The majority of artifacts that have survived two or three hundred years––paintings, furniture, silver, quilts, books, pottery, decoys, tools, and nearly everything we now have from the colonial period––have been relocated to museum settings and other collections. An American colonist, reincarnated and walking through the streets of his hometown today would be hard put to find anything he recognized except the town’s old burying ground. There he would see stones he knew, still grouped by family and bearing familiar names and verses.

Stranger, stop and cast an eye

As you are now, so once was I

As I am now, so you will be

Remember Death and follow me

Death is debt

To Nature due

That I have paid

And so must you

Photo here

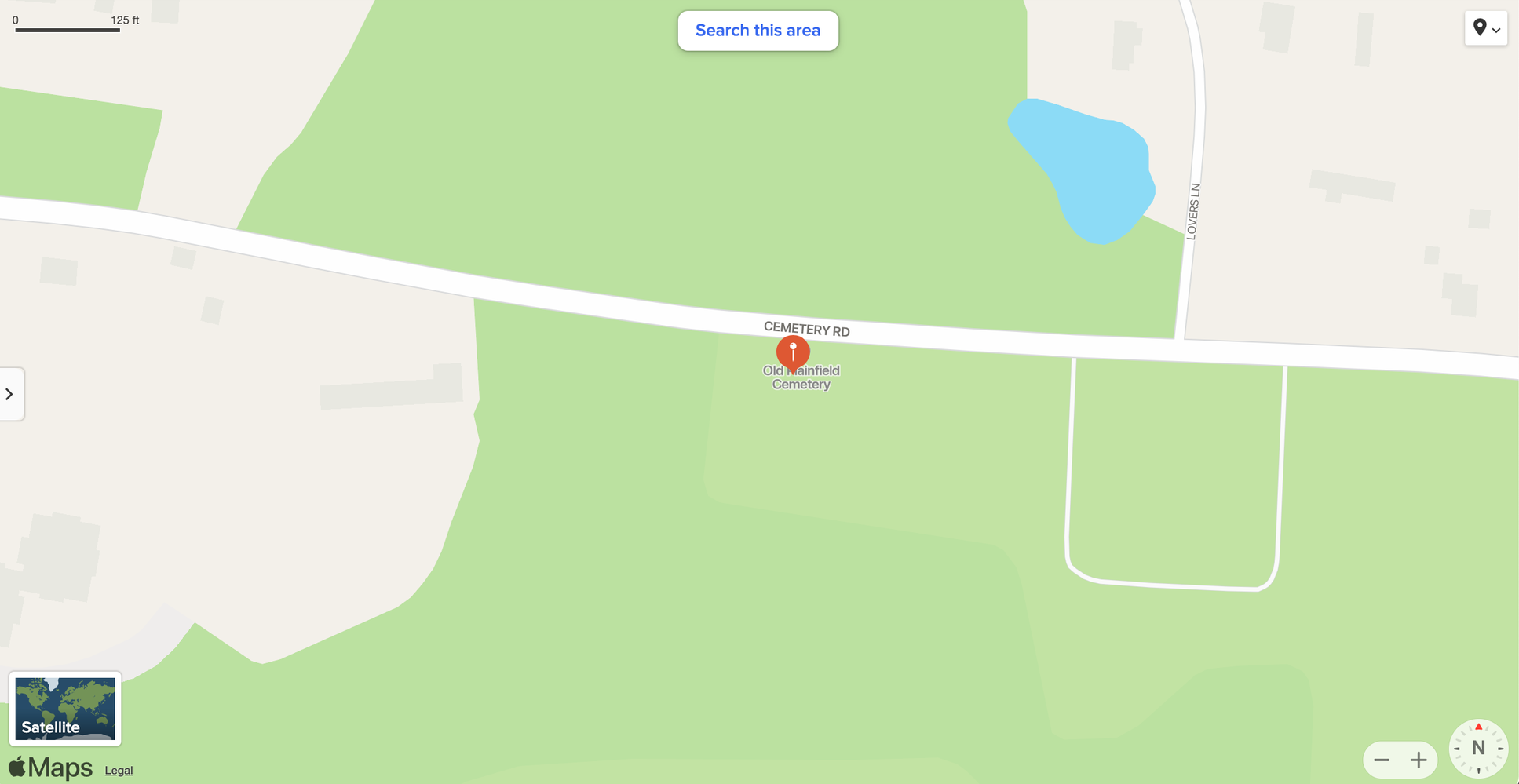

Where are the colonial burying grounds?

Photo here

North America’s seventeenth- and eighteenth-century burying grounds are scattered along the continent’s eastern seaboard from Nova Scotia to Georgia wherever there were settlements, with the largest and oldest yards in the oldest cities.

Today the old stones can be found in both urban and rural settings. Yards are frequently located adjacent to a church or meetinghouse (or where one used to be), or on a town common. They are also tucked between tall buildings, scattered through open fields and remote wooded areas, and huddled near busy airports and throughways––or anywhere the early settlers once lived. Often the stones stand on hills, possibly symbolic of a nearness to God, but more likely a reflection of the settlers’ thrifty use of arable land.

Have early American graveyards changed over time?

The seventeenth- and eighteenth-century graveyards one visits today look remarkably similar to the yards seen in old paintings and drawings of the period. Even then, many of the stones were tilted, sunken, or broken. Then as now, mature trees sheltered the yard, and (without the help of the power mower) tall grass and brush and brambles grew between the stones. The headstones usually faced west; that is, the headstones’ inscriptions faced west, the footstones’ east, with mounded graves between the pairs. We see far fewer footstones now; many have been discarded or reset back-to-back with their headstones to facilitate mowing. Also, in many instances, the headstones have been moved from their original crowded and random grouping and reset in rows or some other formal arrangement. The terrain has often been leveled, again to facilitate upkeep. The features that distinguish an old yard whose stones are in their original positions from one whose layout has been “improved” are the facing and arrangement of the stones and the presence of footstones to go with the headstones.

One can identify the oldest section of a cemetery that spans many years and see how it grew by noting the appearance of the stones––their color, shape, size, and placement. The oldest stones, made of fieldstone, slate, sandstone, schist, or whatever kind of stone was quarried nearby, tend to face west, and (unless they have been moved) they stand grouped together closely and rather haphazardly, like a family, with the taller stones for the most important citizens and tiny stones for children. As it became easier to transport stone, the color and texture of the markers often changed from that of the earliest stones, and with the change of material, the stones’ shape, size, and decorative carving were altered. In burial grounds whose use continued into the nineteenth century, one can see that white marble became the stone material of choice. The middle ears of the nineteenth century saw the introduction of the rural garden cemetery, with spacious, parklike landscaping designed around gentle hills and tranquil lakes. Winding carriage drives led the visitor to fenced family plots filled with ornate, unrestrained, and visibly sentimental three-dimensional sculpture, obelisks, and mausoleums.

Thus, in our burying grounds and cemeteries, we see the sternness of the Puritan seventeenth century replaced by the “Age of Reason” of the eighteenth century, and that in turn replaced by the nineteenth century’s extravagance, love of nature, and free expression of sentiment. The twentieth century, punctuated by two world wars and a depression, is by comparison secular, straight-forward, and businesslike. Death has become more distant. Advances in medicine have lengthened our lives and moved death out of sight, to an unfamiliar, impersonal hospital setting. Our arts embrace abstraction, and in our cemeteries, functional simplicity and anonymity reign. Most contemporary cemeteries are filled with rows of sensible, durable monuments of polished granite. Some modern cemeteries permit only lawn-level bronze markers. At the same time, there is a developing recognition of a need for more individuality and distinctiveness in our lives, and this is beginning to be seen in our art as well––and in our cemeteries. It is possible that cemetery memorials of the twenty-first century will involve changes as significant as those of the past.

Photo here